Venus Anadyomenes

House of the Marine Venus, Pompeii. National Archaeological Museum of Naples in Naples. c. 79 CE. Fresco.

This fresco was found on a panel of the exterior peristyle of a wealthy household, a public space where the men of the house might receive business clients or entertain guests. Venus appears over life-sized, as she rises out of the ocean on a half shell. Flanking her are small, nude boys, one riding a dolphin on her right and another appearing behind the shell by her feet. The boy on the dolphin holds a staff with a flag across his shoulders with fabric draped over his left shoulder. The boy at Venus’ feet is winged and appears without drapery. His placement at the feet of Venus and his wings indicate he is most probably Eros, a member of Venus’ entourage in Roman myth. A similar figure has been identified in the fresco cycle at the Villa of the Mysteries, also in Pompeii and also religious in nature (Kleiner 43).

Venus is shown with a typical Pompeian hairstyle as seen in other frescoes, such as the wife of Paquius Proculus, with curled strands framing her face and a head band to push the rest of the hair back out of sight. Her jewellery consists of a single strand gold necklace, bracelet and anklets with little ornamentation. These are also typical of the jewellery seen in Roman portraits at Pompeii. It would seem that Venus has been depicted in the guise of a wealthy Roman woman. While it was common for Greek men and women to have their portraits completed in the guise of a god or mythological character, in Roman art at this time it was less commonly done and certainly it was rare for a Roman woman to be depicted naked. Rather it is more likely that this Venus is not a veristic portrait of a particular Roman lady, but is shown in the costume of one in order to enforce her connection to the Pompeian community.

While this Venus has many ‘Pompeian’ features, it should be noted that her presentation on the half shell and the drapery that floats above and around her creating a canopy, has strong roots in Greek art. In fact, this fresco is thought to be based on a Hellenistic painting, possibly the birth of Venus as painted by Apelles which is mentioned in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (Grant 61). Recreations of Greek paintings in other medium were certainly popular in Pompeii as demonstrated by the Alexander mosaic which depicts Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issos, and was originally painted by the Greek Philoxenos in the late fourth century BCE (Kleiner 36).

It appears that the Venus Anadyomenes is a mixture of older Hellenistic art and Pompeian sensibility. This rendering of Venus as a contemporary Pompeian women shows the patron’s desire for a connection to the Greek artistic legacy, if not religion as well, while not just revering it as a bygone institution but updating the subject matter so that it was relevant for their contemporary society. Later Roman artistic tradition often coupled veristic portraiture with idealist bodies, although this is most commonly seen in the portraiture of important Roman males (Christ 24). Venus was the Roman patron goddess of sexuality and Eros was her helper who brought sexual desire to men and women who prayed for their help. This is just on example of a female being connected with sexuality in Roman culture. The fact that Venus induces and controls sexual desire and potency brings agency to the seemingly passive figure on the half shell. Also her helper, Eros, hides behind her making it clear that she is the one in control. In this example, female agency is not immediately clear to the viewer through the image. Rather the frame of Roman religion, which intimates that a woman rising out of the sea and accompanied by a young winged male represents the goddess of sexuality, when applied to this image implies the agency of the female.

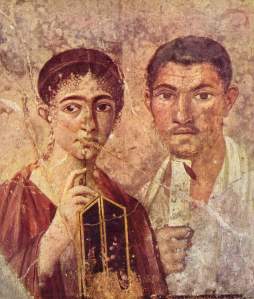

Paquius Proculus and His Wife

House VII, 2.6, Pompeii. c. 13 CE. National Archaeological Museum of Naples in Naples.

As a sign of wealth and status, commemorative portraits were often painted in Pompeii upon the marriage of a couple (Kleiner 149). This fresco depicting Paquius Proculus and his wife was completed as a mural painting in their home and the medium adds an air of permanency to this union, as fresco requires the image to literally become part of the wall it is completed on.

The medium of buon fresco is composed of pigment suspended in water and then applied to wet lime plaster. Once the pigment and plaster dry, they become part of the structure of the building. The nature of this technique requires that the artist works quickly and only in small patches called giornata (Pierce 40).

In addition to the image in buon fresco, a layer of secco fresco is often applied for touch-ups and to fill in details. Secco fresco is less stable than buon fresco and is known to flake (Pierce 40). This instability is a result of the pigment being suspended in a binding medium and then applied to dry plaster, forming a layer of paint on top of the plaster rather than a fusion of paint and plaster. The plaster was created by mixing lime with sand and water for the under layers and marble dust for the top layers. Some frescoes had up to seven layers of plaster applied before the paint layer was begun (Kleiner 41). The fact that marble was used in the preparation of the surface, as well as the amount of time that a fresco would have taken to execute indicates that the patron must have been wealthy to afford such decoration.

A citizen couple, Paquius Proculus and his wife are fully dressed and bear the markings of educated and wealthy Romans, mainly the stylus and scroll and toga of Paquius Proculus. Although, or perhaps because they were man and wife, they are not shown in a sexual scene and there is no visual sign of their relationship aside from their physical proximity, which places the wife in front and very near her husband as they crowd the frame of the image.

The Roman wife is depicted on a light tan background, wearing a deep red dress. She wears a hair band, much like the Venus Anadyomenes, which allows loose curls to frame her face, while holding the rest of her dark hair back. She wears little jewellery and only a pair of drop earrings are clearly shown. She holds a stylus up to her pursed lips with her right hand and holds a writing tablet in front of her chest with her left hand. She sits with her body turned at an angle but her head is square towards the viewer. While her face is realistically modelled and care has been taken to show identifying details, such as her high cheek bones and her dimpled chin, the voluminous fabric of her cloak and dress drape so loosely off her body that her form is almost completely obscured. Both her and her husband are depicted in a half-length portrait which denies further identifying anatomical details such as height and build.

Further than the restriction of view, is that common ancient props have been included in the image as signs for the viewer. Kleiner notes that it was common for the middle class to include the stylus, tablet, toga and scroll in their portraits to indicate education and status, whether or not the couple actually possessed these things (149). In fact there is nothing personal or identifying about the couple from chin down, and it is only in the careful handling of their features that the viewer finds signs of individuality.

Paquius Proculus is shown to have a flat nose with upturned lips and a sparse moustache. His eyebrows are far apart and his forehead wrinkles as he stares out at the viewer. Another identifying feature is his ears which project noticeably outwards. Paquius wears a toga with one end slung around his neck to emphasis its presence. The toga was a visual sign in Roman society to indicate citizenship and status since the time of the Republic (Kleiner 52). In contrast to his wife, he holds his scroll in a passive manner, while she draws the stylus to her lips as if she has paused in her writing to contemplate what to write next. Paquius, on the other hand, holds the scroll still rolled up indicating that the viewer has not interrupted him in the act of reading. Perhaps this is due to the limits of space and convention. However, to take this examination one step further it should be noted that the act of writing, as a form of creation, is more active than that of reading to being with. Here the more active, creative pastime has been assigned to the woman, whether or not she actually partook in it in her real life.

In this fresco the willingness on the part of the patron to mix veristic portraiture with stock images is visible. Although the artist has been careful to faithfully render his subjects facial likeness, their bodies and the objects included in their portrait are used to more or less purely as signs for the viewer. They use stock symbols, such as the stylus, toga and scroll, to indicate the status, actual or desired, of the couple. They present themselves as educated, wealthy, important citizens in the most common way. The use of conventions, especially when mixed with more realistic elements, will again be examined as the representation of the female and her agency is explored in other images.

Images

All the images that follow were owned or commissioned by the middle and upper classes who lived at Pompeii in the 1st century CE. Unfortunately, the home of the lower classes, with the exception of a few apartments over shops, have not survived. Michael Grant proposes that their homes were not sturdy enough to survive, and this seems a valid conclusion (Grant 51). In light of this, it should be noted that these selections were taken from the collections of the ruling faction in ancient Pompeii. A distinction has not been made about the identity of the patrons of these frescoes, as it is still very difficult to know with any certainty the owner of the surviving buildings. The exception is the tentatively name Paquius Proculus and his wife fresco. For the purpose of this study, however, it is enough to know that these images were commissioned by wealthy patrons which is evident through the very fact that their homes or bath buildings were well-built enough to survive the eruption and because the medium of fresco requires great skill, time and expensive material. Finally, this study employs the names of the paintings as given by the Naples National Archaeological Museum where available and more descriptive and ultimately pertinent information has been given in the images captions and analysis.

Pornography in the Beginning

In the Classical world, pornography was not a specific genre of expression but rather explicit sexual material could be found in almost every genre of poetry, prose, painting, and theatre (Parker 91). There was only one genre that was uniformly sexual in nature and that was the an-aiskhunto-graphoi, a form of erotic handbook written to instruct its reader on the various sexual positions recommended for heterosexual intercourse (Parker 91).

Holdt Parker argues that if, as a modern audience, we define pornography as the representation of sexual encounters where there is a clear power structure in play, that of the dominator/aggressor and the dominated/passive, than almost all Classical erotic depictions and attitudes will appear pornographic in nature (100). Parker also posits that pornography, or rather discourse on sexuality in the ancient world was a way for civilized culture or the masculine essence to subdue and subjugate nature or the feminine essence (102). Sex, as a phenomenon that exists pre-civilization, is here ruled by the discourses within which ancient men contain it. Although Parker addresses mainly the an-aiskhunto-graphoi, the same kind of action happens within these sexual frescoes. When displayed in homes or public places they reinforce social mores and expectations when it comes to sexual relationships. However, upon closer inspection these images seem to explore further the agency and power relationships of intimate encounters beyond the usual woman as passive/man as active dichotomy. In fact in most of the images examined, women are emphasized as the active subject, either by engaging the viewer through their direct gaze or their dominant positions. Although these images do seem to associate women with the ‘naturalness’ of sex they are not being subdued by civilizing men, but rather act as a force of nature, powerful and active.